Here's a good Chicago trivia question for you.

It's a picture clue:

In this view looking up Michigan Avenue from Monroe Street, three of the buildings pictured were at the time of their construction, the tallest building in Chicago. Name them.

I bet you can't. Well at least I couldn't name all three a week ago, as at least one of my picks would have been wrong. That in itself might be a clue, but I'll get to that in a minute.

Years ago, the syndicated columnist Sydney J. Harris used to have a regular feature called "Things I Learned on my Way to Looking up Other Things." That was back in the day before the internet when you'd look through a general interest reference book, perhaps an encyclopedia, and come across information that might catch your eye that had absolutely nothing to do with what you were looking for. Internet searches are more focused, so if the web is your primary source of information, you're less likely to be looking up say, gestation periods of mice, and find yourself engrossed in an article about the Gettysburg Address.

But I digress. As I was looking up information for an earlier post on the Sears/Willis Tower on the

Emporis website, I came across a link that listed the chronology of the tallest buildings in Chicago, beginning in 1854.

It turns out the same list can be found on

Wikipedia, which is what I copied here:

| Building |

Dates as tallest building

in Chicago |

ft (m) |

Stories |

|---|

| First Holy Name Cathedral |

1854–1869 |

245 (75) |

1 |

|

| Saint Michael's Church |

1869–1885 |

290 (88) |

1 |

|

| Chicago Board of Trade Building | 1885–1895 |

322 (98) |

10 |

|

| Masonic Temple Building |

1895–1899 |

302 (92) |

21 |

|

| Montgomery Ward Building |

1899–1922 |

394 (120) |

22 |

|

| Wrigley Building |

1922–1924 |

438 (134) |

30 |

|

| Chicago Temple Building |

1924–1930 |

568 (173) |

23 |

|

| Chicago Board of Trade Building |

1930–1965 |

605 (184) |

44 |

|

| Richard J. Daley Center |

1965–1969 |

648 (198) |

32 |

|

| John Hancock Center |

1969–1973 |

1,127 (344) |

100 |

|

| Aon Center |

1973–1974 |

1,136 (346) |

83 |

|

| Willis Tower |

1974–present |

1,451 (442) |

108 |

Now if you know your Chicago buildings, you'll realize that the three buildings in my picture on the list of one time tallest buildings in the city are the

Aon Center, (formerly the Standard Oil Building, the tower on the extreme right), the

Wrigley Building, (the bright white building which you can see off in the distance in the lower left quadrant of the picture), and the

Montgomery Ward Building, (also known as the Tower Building, the third building from the left).

The list contains a few surprises in its omissions. If you're an old time Chicagoan like me, you might be surprised that the

Prudential Building, (or One Prudential Plaza as it's now called, the Mid-century Modern building with the huge antenna), is not on the list. Between the time it was built, 1955, until the construction of the

John Hancock Building on North Michigan Avenue in 1969, most people in town assumed the Prudential was the tallest building in the city because it featured an observation deck, and pretty much billed itself as such. Mea culpa, I declared it as Chicago's one time tallest in my appreciation of the building in

this blog post. There I called it "the tallest building in the city and the most prominent building in the skyline." Well at least the second part was true. The first part was partially true, as the Prudential did once have the tallest roof and highest occupied floor in the city. But if you count the statue of the goddess Ceres atop the

Chicago Board of Trade Building on La Salle Street, as the folks who compile building height stats do, that 1930 building is taller, by all of four feet! It became a moot point when the

Richard J. Daley Civic Center was built in 1965, a full 47 feet taller than the Prudential. Still the top of that building is devoted to mechanical equipment so the Prudential still could claim the highest occupied floor in Chicago until 1969.

These may seem trivial distinctions until you consider the brouhaha over

One World Trade Center in New York City, which was completed in 2014. The roof of that building is 1,368 feet above the ground. The roof of

Sears/Willis Tower in Chicago is 1,450 ft. The difference is that One World Trade has a decorative mast on top of the building, which looks very much like an antenna, bringing the total package from ground to pinnacle, to 1,776 feet, an easy number to remember (no coincidence there). There was a

huge debate at the time between backers of the two cities over which town's building was taller. The official arbiter of such things, the

Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, determined that the thing on top of the New York building was indeed an architectural element, as opposed to a an antenna, which meant it counted toward the building's official height, making it by decree, taller than the Chicago building.

Here, on their site you can read about their criteria, which is in agreement with the Chicago list which takes into account architectural elements like church spires and statues atop buildings, but not antennas and other purely functional elements.

Another surprising omission from the list is William LeBaron Jenny's

Home Insurance Building. Topping off at 138 feet, the ten, later twelve story 1884 building was dwarfed by the 290 foot steeple of St. Michael's Church. Yet the significance of Jenny's building is far greater than the church steeple as it was the first tall building to have been supported both inside and out, by an interior fireproof metal frame. Ask any dyed-in-the-wool Chicagoan and he or she will proudly tell you that Jenny's building was the "world's first skyscraper." Given the term, one would assume that distinction alone would make it, upon its construction, the city's if not the world's tallest building. It wasn't even close. However "skyscraper" is not a technical term describing a particular construction technique, but a relative term that describes any tall building in relation to its surroundings. In Chicago, a city with today, perhaps 100 buildings with more than 50 stories, no one would call a new ten story building a skyscraper, regardless of how it is constructed.

Beyond their usefulness for providing esoteric facts and trivia game answers, if you actually put some thought into them, lists like these can be useful tools in the study of the history of a city. One might reasonably assume for example, that the tallest building in a city at a given time is an indication of the relative importance of the institution that built it. For example, if you look at the list of the chronology of the tallest buildings in Chicago, you'll notice that in the early years, the tallest buildings were churches. You might conclude that Chicagoans at the time were more concerned about building temples to God than to Mammon. This in fact is an interesting topic which has no simple answer, it is the jumping off point for such disparate topics as19th Century religion and building technology.

There is a practical reason why commercial buildings were not as tall as church steeples in the mid-nineteenth century; the first passenger elevator wouldn't appear in Chicago until the mid 1860s. Before that, it was simply unfeasible to build "walkup" buildings above a certain height as no tenant would rent a space where they'd have to climb more than six or seven flights of stairs to get to their office or home. Church steeples on the other hand, could be built at the discretion of their congregations, to great heights, some of them exceeding the height of a present day twenty story building. The taller the steeple, the greater the prestige of the congregation, and also the neighborhood in which it stood. While religion certainly wasn't the centerpiece of early Chicagoans ' lives, the presence of churches in a community gave at least the appearance of cultivation, that contrasted with the get-rich-quick, no-holds-barred, boom town mentality of Chicago, the necessary yin to the young city's yang, so to speak. In the 1860s, the great landscape architect

Frederick Law Olmsted cynically wrote in his journal:

A church steeple will be built higher than it otherwise would be because the neighboring lot holders regard it as an advertisement of their property. There is nothing done in Chicago that is not regarded as an advertisement of Chicago.

|

Spire of St. Michael's, Old Town

The tallest of tis kind in Chicago |

With the introduction of the elevator and William LeBaron Jenny's technical innovations, multi-story buildings could now be as tall as the economic conditions of the time permitted. As commercial buildings grew taller, church steeples did not. With the exception of the 1924

Chicago Temple Building which features a church steeple placed atop an office building, (a unique temple to both God and Mammon), the tallest stand-alone church steeple in Chicago is still

St. Michael's in Old Town (not to be confused with

St. Michael the Archangel Church, another landmark church with an enormous steeple that defines its community, South Chicago). After the destruction of the

Church of the Holy Name in the Great Fire, the steeple of its successor,

Holy Name Cathedral, would be several feet shorter than it predecessor's. Rather than compete for height with the new skyscrapers, church congregations in Chicago found new ways to distinguish their houses of worship, such as placing them adjacent to parks and other open spaces.

When I first conceived this post, my idea was to simply print the Emporis/Wikipedia chronology list

accompanied by some comments and contemporary photographs of the nine extant buildings, and historical photographs of the three that have been lost. In doing a little background research, I opened up my copy of the

Encyclopedia of Chicago, to their entry on skyscrapers. That article included the book's own chronological list of the city's tallest buildings. To my surprise, their list doesn't quite match the Emporis/Wikipedia List. Here is the Encyclopedia of Chicago list, as borrowed from their web site:

| Building |

Date |

ft |

Stories |

Address |

|---|

| First Holy Name Cathedral |

1854 |

254 |

1 |

733 N. State Street |

| Water Tower |

1869 |

154 |

1 |

800 N. Michigan Avenue |

| Holy Family Church |

1874 |

266 |

1 |

1080 W. Roosevelt Road |

| Masonic Temple |

1892 |

302 |

21 |

State and Randolph, NE corner |

| The Tower Building |

1899 |

394 |

19 |

6 N. Michigan Avenue |

| Wrigley Building |

1922 |

398 |

29 |

400 N. Michigan Avenue |

| Chicago Temple |

1923 |

568 |

21 |

77 W. Washington Street |

| Chicago Board of Trade |

1930 |

605 |

44 |

141 W. Jackson Boulevard |

| Richard J. Daley Center |

1965 |

648 |

31 |

50 W. Washington Street |

| John Hancock Tower |

1969 |

1,127 |

100 |

875 N. Michigan Avenue |

| Aon Center |

1973 |

1,136 |

83 |

200 E. Randolph Street |

| Sears Tower |

1974 |

1,450 |

110 |

233 S. Wacker Drive |

Two buildings on the Encyclopedia of Chicago's list are not on the Emporis list, the

Water Tower, in place of St. Michael's Church, and

Holy Family Church, rather than the old Board of Trade. Now if you look closely at this second list, there is something curious about the inclusion of the Water Tower. Built in 1869, the Water Tower's height of 154 feet is exactly 100 feet shorter than the building it succeeds, the old Church of the Holy Name. That church was destroyed in the Great Fire while the Water Tower stands to this day, so it makes sense that as the tallest building left standing intact, the Water Tower would have succeeded the church as the tallest building in the devastated city. But the fire took place in 1871, so I can only conclude that the 1869 date is a mistake.

|

Holy Family Church

Prevailing SW winds on the night of

October 8, 1871 prevented this

great west side church from being

consumed by the Great Fire which

started only one half mile away. |

Holy Family Church, built in 1860, also survived the Fire, apparently in answer to

Father Arnold Damen's prayers that the church he built to serve Chicago's burgeoning immigrant Irish population of Chicago's west side, be spared. Whether it was divine providence or merely the strong southwesterly winds that steered the flames away from his church, less than a half mile from the source of the fire, to this day lights are lit at the shrine of Our Lady of Perpetual Help inside the sanctuary of Holy Family in eternal gratitude that the church was saved. The reason why the the

Encyclopedia of Chicago's date for Holy Family succeeding the Water Tower is 1874, rather than its construction date, was answered for me by

Father George Lane and his seminal book on the subject,

Chicago Churches and Synagogues: An Architectural Pilgrimage, which points out that the spire of Holy Family wasn't completed until 1874.

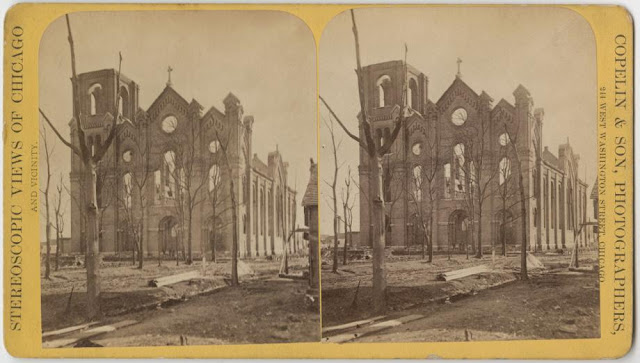

But what about the spire of St. Michael's, which is 24 feet higher than Holy Family's? Unlike Holy Family, St. Michael's was directly in the path of the fire. As this stereo-photograph of the devastation of St. Mike's shows, had there been a 290 foot tower at the time of the fire, it did not survive.

Confirming what's visible in the stereograph, in his book, Father Lane notes in his book that the fire, "... gutted St. Michael's leaving only the walls and part of the tower standing." According to Lane, the great spire and landmark of the near north side of the city wasn't completed until 1888. I haven't been able to ascertain whether the pre-fire tower was the same height as the one we see today, but it simply cannot be true that the church could claim title of city's tallest structure between October, 1871 and 1885 as the Emporis list claims.

I have no answer at the moment why the Encyclopedia of Chicago omits the old

Board of Trade Building from its list. Here is a photograph of it standing on the same site as its Art Deco successor, where LaSalle Street meets Jackson, with the estimable

Rookery Building visible on the left. Again it is the tower which puts this building over the top. The old Board of Trade lost its distinction as tallest building in the city in 1895 when its (in my opinion) inelegant clock tower was removed. The opulent building designed by

W.W. Boyington, the architect of the Water Tower and many other mid-nineteenth century Chicago buildings, was demolished in 1929 to make way for its successor.

The real mystery surfaced when I began to assemble historic photographs of the buildings on these lists. Although its great size encouraged the Archdiocese of Chicago to use it for official diocesan ceremonies, the

Church of the Holy Name, built in 1854, was, contrary to what it is called on both lists, never Chicago's official Roman Catholic cathedral. That distinction went to

St. Mary's Cathedral in the Central Business District, what today we call the Loop. Holy Name was built in conjunction with the original

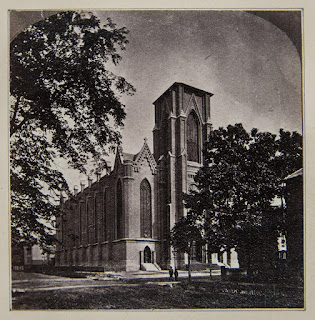

St. Mary of the Lake University, Chicago's first university. Continually plagued with debt, both the university and the church struggled to keep afloat, and the university closed its doors in 1866. (The university re-opened in 1926 as St. Mary of the Lake Seminary in the Chicago suburb of Mundelein, IL). The photographs I found of old Holy Name Church were few and far between, but I was unable to find a single photograph with a tower anywhere close to the advertised 240 feet. I don't have the dates on these first two pictures but based upon what I learned, more on that later, I'd say the first photograph was made around 1862, give or take a couple of years.

You can clearly see the base for what would be the tower, hadn't yet reached much beyond the roof line of the church. The next picture shows the second stage of construction of the tower complete. I'm guessing it had to have been made not more than a couple years after the first, judging by the height of the tree on the right:

The date of the next picture is certain, the fall of 1871, shortly after most of the church was destroyed by the Chicago Fire. In this picture you can see the third stage in the development of the tower, and two beams protruding from the top, suggesting that there was indeed some kind of structure above:

Granted it's true that the documentation of the buildings of pre-fire Chicago is inconsistent, but the idea that I couldn't find one photograph of the completed spire perplexed me, especially if it was indeed the tallest structure in Chicago at the time. Unfortunately Father Lane in this case was no help. In his entry on the current cathedral which replaced old Holy Name, he only devotes one sentence to the lost church.

Another book I had on my shelves,

Constructing Chicago, by Daniel Bluestone, devotes an entire detailed chapter to the construction of pre-fire churches in Chicago, but was also of no help regarding the specifics of the tower at old Holy Name.

I also managed to find an old souvenir book on my shelves, published in 1949 on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the founding of Holy Name parish. I got the book at the cathedral at the re-opening ceremony after the church was closed because of damage due to a fire in its roof, I think they were giving copies of the book away just to clean house. Anyway, that book contains a very detailed history of the city of Chicago, told of course from a very Catholic point of view. Turns out the very first cathedral of Chicago was actually the magnificent

Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin in Baltimore, designed by

Benjamin Latrobe in 1821. Back in frontier days when Chicago was just a backwater settlement, the territory covered by the archdiocese of Baltimore extended all the way to the Mississippi River. The Chicago diocese was founded in 1843. This book didn't go into great detail about the church building either, but it did give a detailed account of the parishioners who donated the money to build it and how much they gave. It also provided an eye-witness account of its destruction which describes the steeple catching fire, then collapsing onto the roof of the church, setting it on fire. That account was my first evidence that the spire actually existed.

Then I remembered a photographic panorama of Chicago made from the tower of the old Court House Building in the center of town. The panorama was published in the book

Chicago, Growth of a Metropolis by Harold B, Mayer and Richard C. Wade. In the section of the panorama pointing northeast, three towers are clearly visible. One is the Water Tower, which had yet to receive its distinctive cupola, the tower of

St. James Episcopal Cathedral, which also survived the fire and the subsequent 146 years, and low and behold, the base of the tower of Holy Name Church, looking very much like it did in the second photograph, with no spire. Although the photo does not show the towers clearly as they are at least one mile from the camera, it does appear there is work taking place, probably the construction of the third stage of the tower. As the Water Tower was built in 1869, the date of this photograph has to be between 1869 and 1871. Since the city at the time was filled with many 200 ft spires, the assertion that Holy Name was the tallest building in Chicago since 1854, has to be incorrect.

I asked myself, was there ever a tower? True, there was the account of the burning tower crashing onto the roof of the doomed church, but that was a scene repeated over and over again during those dreadful two days of the fire. It occurred to me that perhaps the eye-witness, in all the stress of a huge city burning before his eyes, could have mistakenly been recounting the story of the destruction of another church.

I was prepared to leave the question open until I decided to trudge through the tedious prose of the souvenir book. Reading through the histories of a succession of Chicago bishops with delicate constitutions who met their maker many years before their time, I discovered that in 1863, under the episcopate of one of those unfortunate men,

Bishop James Duggan, the pastor of Holy Name, Father

Joseph P. Roles:

...undertook with the permission of Bishop Duggan to add to the interior decorations which others had left incomplete. He installed the main altar and two side chapels with their screens, the altar railing and the pulpit, all in hand carved walnut. He also started to build the steeple which was originally planned. This was still in progress when the Church of the Holy Name was burned to the ground in 1871.

So there you have it. My guess is that the process of adding segments to the tower began in 1863 and continued, probably sporadically since those were war years, at least through 1869 or 1870, when work on the steeple above its supporting tower began. The first photograph was probably made just before 1863 and the second, sometime not long after 1865. From the information I have, at the time of the fire, the steeple may or may not have reached its planned 240 foot height, but the account of the destruction of the church mentioned above is most likely true.

Given all that, the Church of the Holy Name could not have been the tallest building in Chicago before 1869, and given that the steeple was not completed at the time of its destruction, its status as tallest building in Chicago at any time is doubtful.

Coming across that information the other day was a little bit of a letdown, I had anticipated doing some more legwork tracking down the story of the phantom tower of the Church of the Holy Name, and learning more about the history of the city along the way. As with many research projects, the journey is more satisfying than the destination. There's no real joy in debunking the notion that the Church of the Holy Name once had the distinction of being the tallest building in Chicago. Had it not been for the Great Fire, it very well may have been, for a little while anyway.

I don't know why but trivial as it may be, knowing that fact makes me a little sad.

The good news is if the spirit moves me, I can now embark on a project to discover the actual tallest buildings in Chicago before the Great Fire.

If I ever get the time.

,

,